A rough landing in Hudson Bay

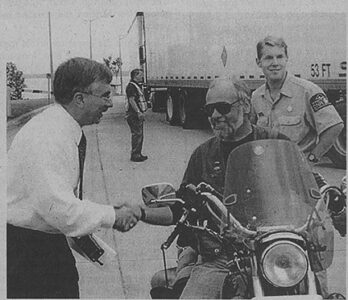

Courtesy Photo William Kelley’s airplane is seen tied down near a grassy airstrip in Hudson Bay, Saskatchewan in 1971.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is the 11th in a series of stories adapted from William Kelley’s book, “Wind Socks, Grass Strips, and Tail-Draggers.” Last week, after being laid up overnight by a storm, Kelley hitched a ride to the Neepewa, Manitoba airport.

Fields and pothole lakes passed beneath me as I headed for Yorkton, Saskatchewan.

The greenish-yellow fields were of spring wheat. By that time in July, our fields of fall wheat are bright gold and ready for harvest. The bright yellow crop that I’d thought was wheat was the crop known as rape. At close range, it could pass for what we call mustard, a weed with black round seeds that resemble buckshot, which grows wild in our part of the country.

An hour and 20 minutes after takeoff, I crossed the border near the towns of MacNutt, Saskatchewan, and Dropmore, Manitoba. Visions of how those names were derived passed through my mind. Clouds had begun to form in the sky.

Thirty minutes after I made the terrific discovery that “God is alive and well; I found him yesterday lurking in cloud columns across the prairie,” Yorkton came into view.

When I go into strange territory, it is my practice to inquire of those who fly and know the area as to conditions at the various airports and any quirks I should know.

The folks I wanted to see in Saskatchewan lived near the town of Carragana. I asked about airports nearby and was informed that only private strips are anywhere close. The best bet would be to land in Hudson Bay, a ways east of where I wanted to visit.

I called the folks and told them where I was, where I intended to land, and about when I would be there. She said Andy was in the field. By the time he could eat and clean up and get to Hudson Bay, it would take two hours. That seemed about right.

Hudson Bay, Saskatchewan is near the northeast corner of nowhere. Several miles east of town, a road runs north to Flin Flon. It is a major artery that connects the southern and northern regions of the province.

The road that runs the 50 miles from Hudson Bay to my friends’ farm is one of the northernmost east-west roads in that part of the province. They farmed north of there another 75 miles early in their farming days. The railroad was the major means to transport goods, as it is throughout much of Canada.

Permafrost and extreme winters had driven my friends south to farm in Carragan, near Porcupine, Saskatchewan.

At one point, I flew at 3,200 feet and saw something in the sky about the same altitude. Suddenly, a pair of red-tailed hawks darted past the left wing, about 70 feet off the port side. The wind made the plane rise and settle, lazy-like. The hawks glided and banked on the updrafts. I felt like one of them.

Finally, Hudson Bay bloomed before me on the horizon. After wondering if I was ever going to find it in all that wilderness, there it was. It was set in trees, surrounded by water, fitting for a town whose industry is lumber and a few minerals.

The runway at Hudson Bay wasn’t exactly on an airport. It was on the east edge of a golf course and ran north-south. The winds, judged by the smoke over town, were from the south. Since the strip wasn’t exactly long, I wanted to set up properly for a good landing. The downwind leg was established east of town and base leg was right over town. Final approach was established by lining up a tall smokestack with the end of the runway.

I descended toward what appeared to be the tallest trees in the area. By the time I was low and slow enough for a landing, I was halfway down the runway. I pushed the throttle forward, pushed in the carburetor heat, and went around.

Except for using full flaps on final approach, the second pattern was the same as the first. This time, using those full flaps, I aimed for the very end of the runway, even though I was sure the trees would prevent my descent.

The flaps did allow for a greater angle of descent. Over the end of the runway, I cut the power. Slowly, the plane descended and I was on the ground — well, I was for a few seconds. Then I was airborne. Never had I landed on a surface that was so rough. Balls land in the rough. Planes aren’t supposed to.

It took all my skill and knowledge as a pilot to slow enough to turn around and taxi back to the other end. Gusty winds, rough field, short runway, obstacles at the ends of the runway, all helped to make it a tough landing. But those are some of the items covered by instructors when short field landings and takeoffs are taught.

I was up to the task.

The runway was literally hewn from the forest. I was really excited to finally land at a real unimproved airstrip. It definitely qualified as a grass strip.

Hudson Bay Airport was hacked out of the same forest as the golf course I had circled trying to find the runway. Several planes were tied down, protected from errant golf balls by a patch of trees. That was the only giveaway that led me to believe it was an airport.

The fairway may have been all right for walking, but it was too rough for golf carts. The ground rolled and jutted, uneven even where it was flat. After the plane shook and bounced to a stop, I rolled and rocked back to the tiedown area. No tiedown rings were available for me.

The axe I carried in the plane for survival came in handy. I chopped a small tree, limbed it, and made three tiedown stakes. With the backside of the single-bit axe, I drove them into the ground and tied the ropes I carried for such an emergency. It was as I tied the last rope to the ring of the wing that the folks I’d stopped to see appeared. They had driven their 1953 Buick Century right up to the plane.

Check The News next week for the next installment. William Kelley was a teacher for 32 years and has been a pilot since 1966. He lives in Herron on the family farm where he was born and raised.