Telling a book by its cover

Vignettes

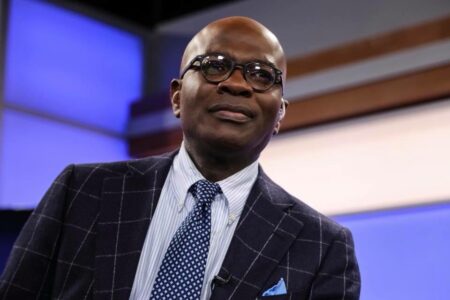

Doug Pugh

It’s hard to tell a book by its cover, but book cover artists are doing just fine.

According to a recent survey, 57% of Americans buy books based solely on their covers. A good book cover grabs attention, conveys a theme, implies a promise, and entices readers to buy.

But covers can be surface sheens, hiding chaos below, like rainbows covering the awkward conversations in receding storms.

Romance novels consistently lead the category in book sales, with their cover artwork often overlooking awkward conversations, instead relying on erotic content. However, books aren’t the only things with covers, nor are they the only things to cover in a discussion of covers.

My mother never said I was handsome, but occasionally she would remark that I had a good-shaped head, relieving me of the need to wear a hat solely for its cover.

The opportunity to cover interesting and essential topics is presented in college course materials, unless you’re from away and attend Harvard, in which case, visa difficulties may be uncovered. If they are, others will covet you for the vigor and diversity your exclusion uncovers.

A cryptocurrency donation can provide cover for a crime.

Medical researchers at our universities follow elusive pathways in their search for cures to the ailments that afflict us, but awful offal from politicians has blocked the towpaths, slowing their progress to a trudge, delaying deliveries.

Much confidential information previously kept undercover is no longer.

There are things about ourselves we keep covered, and things about ourselves we didn’t know were covered. There are awkward conversations we didn’t know we should have.

Dr. Leor Zmigrod was a Gates Scholar at Cambridge. She held fellowships at Stanford, Harvard, and the Berlin and Paris Institutes for Advanced Study and was listed in Forbes’ 30 Under 30 in Science. She is a pioneer researcher in political neuroscience and the author of “The Ideological Brain: The Radical Science of Flexible Thinking” (2025).

Her work has been recognized as a significant contribution to the field of political neuroscience, and her book was named a Best Book of the Year by British newspapers The Guardian and The Telegraph.

Political neuroscience, who knew? You’d never guess it from the cover.

We have lived under the impression that, in the complex mix of operations within our functioning brains, there exists an indeterminate line separating life-sustaining, autonomous functions from reasoning and conscious awareness.

But maybe not.

Zmigrod’s studies suggest that specific brain structures and dopamine distributions can lead to more rigid thinking patterns, making some of us more susceptible to dogmatic beliefs.

For example, diversity and inclusion are at the foundation of our nation’s strength — a strength predicated on the declaration that all people are created equal and the Christian canon embodied in the Golden Rule. Excluding people based on race, gender, and ethnicity will only weaken us.

We live in unprecedented times, in an isolating world our brains are ill-prepared for. We are continuously bombarded by social media “truths” that aren’t. Though they provide easy answers, conformity is demanded.

Zmigrod cautions us to protect our individuality by being aware of our inherent susceptibility to dogmatic thinking.

Armed with that knowledge, we know to test the validity of what would persuade us in a world that strives to mislead us.

We have uncovered the enemy, and, once again, it could be us.

Doug Pugh’s “Vignettes” runs monthly. He can be reached at pughda@gmail.com.