Officials push for new housing, but developers have to have faith

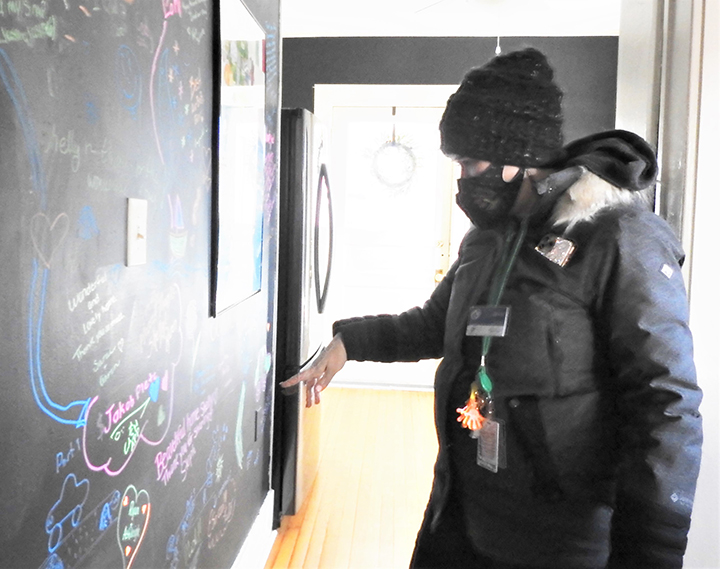

News Photo by Julie Riddle Shelly Katto points recently to a chalkboard in her Alpena Airbnb home signed by a group of nurses who found temporary housing there.

ALPENA — The use of tax incentives, zoning changes, policy revisions, and the creative use of current structures still haven’t kept up with a spiking demand for housing in Northeast Michigan.

Big demand and too little supply, rising construction costs, and limited construction workers — in part because of the coronavirus pandemic — caused the region’s housing shortage, The News learned after weeks of research and interviews with homebuyers, sellers, and real estate and economic development officials. The shortage means people who want to move to or within Alpena often have to wait months before they can land a home.

More than just an inconvenience, the shortage has pushed up home prices, made it hard for businesses to recruit talent, and could hurt the region’s economic development efforts long-term, officials say.

But, so far, the fixes officials have tried haven’t paid off in a big way.

Economic development firm Target Alpena owns property on the Thunder Bay River downtown where officials would like to see three or four stories of residential units developed, with the lowest level dedicated to commercial businesses to meet current zoning rules downtown.

News Photo by Steve Schulwitz Lorie and Chris Lawrence and their children, Kaylee and Mason, pose in the family’s theater room recently. The family built its new home in a Neighborhood Enterprise Zone created by Alpena city officials to encourage new home construction.

So far, nothing’s come of it.

Investors want to know how much revenue they can generate before committing to a project like condominiums or an apartment complex, said Adam Poll, president and CEO at the Alpena Area Chamber of Commerce.

But, without existing housing showing developers such a project could work, the money stays away.

“It is sort of the chicken and the egg analogy,” Poll said. “Developers and financiers want to know what the market and occupancy rates are for things like condos, but we don’t have any comparisons to show them. Someone has to be first to take the plunge.”

‘A WIN-WIN’

News Photo by Steve Schulwitz Adam Poll, the Alpena Area Chamber of Commerce president and CEO, recently shows off vacant property available for commercial and residential development in downtown Alpena. He said the ideal project for the property would feature businesses on the street level and residential units on the floors above.

Governments do what they can to allay developers’ fears.

Hope Network plans to restore the long-vacant Bingham Arts Academy in Alpena into 35 one-, two-, and three-bedroom apartments for low-income residents. The Alpena Planning Commission made the project possible after it agreed to rezone the property to allow for residential construction.

Alpena also uses Neighborhood Enterprise Zones, a state program that allows cities to offer tax breaks to encourage the construction of new homes and the creation of housing units on existing commercial properties.

One zone, just a few blocks from downtown, is running out of building space, and the city could look to establish more.

Chris Lawrence built his new home in the zone last year and called the program a benefit for homebuyers.

“If you can receive a break on your property taxes, I think it will influence more people to build,” Lawrence said. “We chose our lot because it was an Enterprise Zone. Had an eye on it for years, so it was a win-win.”

The city could also consider “up-zoning,” which allows developers to create additional housing on existing lots by building more homes or dividing existing houses into apartments, said Andrea Kares, former Alpena planning, development, and zoning director. Kares left her city position late last month, after the interview for this story.

“There are many lots in the city that would be large enough to accommodate something like that, if they choose to do so,” Kares said. “That could be one potential solution, but it’s not really written into our zoning ordinance at the time.”

Poll, the Chamber president and a former Alpena city planner, said Alpena has utilized Community Development Block Grants from the Michigan Economic Development Corp. to create about 30 rental units, many downtown. When those hit the market, they don’t last long.

“Since those units were completed, I don’t think there has been a vacancy, because they are very popular,” Poll said. “We’re hoping, because we can show the limited vacancy, it will lead to larger developments.”

‘YOU’RE HUSTLING ON A WEEKLY BASIS?’

Many Up North communities have plenty of structures that could be used for new residents, but the properties are tied up as lake cottages, hunting cabins, summer homes, and, more recently, Airbnb and other short-term rental units. Such properties make up 84% of the Northeast Michigan homes without year-round residents, the U.S. Census Bureau says, compared to 44% statewide and 33% nationwide.

Some communities have considered moratoriums on such properties.

Joe Borgstrom, principal with the East Lansing-based economic development consulting firm Place and Main, suggested such a moratorium in Rogers City.

“There’s nowhere for potential employees to go,” Borgstrom said. “One of the ways you can do that is go to those property owners and say, ‘You’re hustling on a weekly basis? Why not just turn it into a regular rental and be able to rent it six to 12 months?’ So, we’re trying to convert that housing into more permanent housing.”

But landlording is a tough business, Shelly Katto told The News. That’s why she now runs an Airbnb.

That allows her to invest in Alpena, she told The News.

Katto’s guests have included short-term medical staff and workers who need housing during temporary projects in the city, such as the recent construction of a new Alpena jail.

‘SPREADS TO A BIGGER VISION’

Fixing the housing crunch isn’t just up to the government, and some local efforts may lead to a slight improvement in the local housing market.

Borgstrom, with Place and Main, said cities can make the most of existing footprint by utilizing upper floors of downtown buildings as apartments, rehabilitating existing buildings so new ones aren’t constructed, and allowing people to build so-called “mother-in-law units” — a small, private living area within a property — above garages or behind their homes

Communities on the west side of the state have made proactive efforts to improve housing, according to Yarrow Brown, executive director of advocacy group Housing North.

From a multi-use, four-story real estate cooperative planned in Traverse City to turning single-family homes into multiple living spaces in Charlevoix to other communities renting empty seasonal homes to employers for temporary worker housing, residents and government on the Lake Michigan shore combine efforts to find creative solutions.

“If it starts with a local organization or housing group and then spreads to a bigger vision, that’s likely to be successful,” Brown said. “Local community advocacy is huge.”

- News Photo by Julie Riddle Shelly Katto points recently to a chalkboard in her Alpena Airbnb home signed by a group of nurses who found temporary housing there.

- News Photo by Steve Schulwitz Lorie and Chris Lawrence and their children, Kaylee and Mason, pose in the family’s theater room recently. The family built its new home in a Neighborhood Enterprise Zone created by Alpena city officials to encourage new home construction.

- News Photo by Steve Schulwitz Adam Poll, the Alpena Area Chamber of Commerce president and CEO, recently shows off vacant property available for commercial and residential development in downtown Alpena. He said the ideal project for the property would feature businesses on the street level and residential units on the floors above.