Court changes may not be enough

Attorney reforms have helped, but total overhaul may be needed, official says

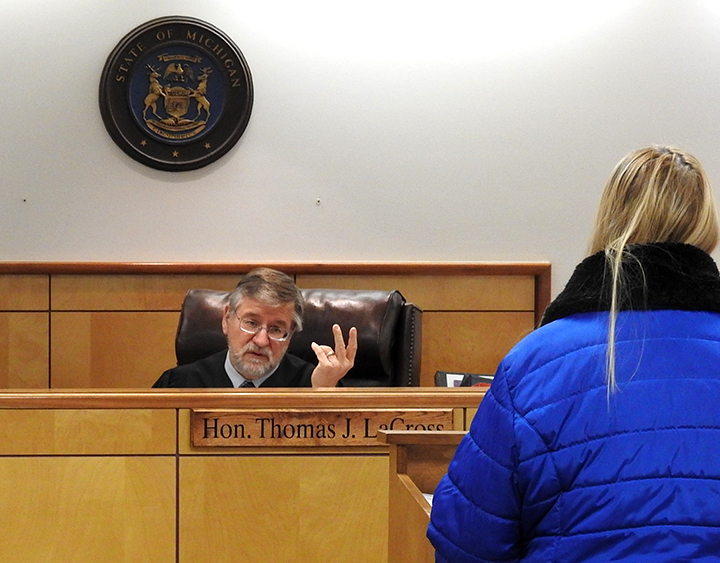

News Photo by Julie Riddle Judge Thomas LaCross speaks to an indigent defendant during a recent arraignment. No longer left to stand before a judge alone, criminal defendants who can’t afford their own lawyer have seen some positive changes in their legal representation in the past year, but officials say there is room for improvement.

ALPENA — Almost a half-million dollars was supposed to help Alpena County do a better job taking care of criminal defendants who can’t afford a lawyer.

However, after state-funded reforms failed to yield the intended results, the county may need to consider restructuring its court-appointed attorney system all together, an official said.

Alpena County received $419,157 in October 2018 from the Michigan Indigent Defense Commission — added to the roughly $260,000 a year the county already paid for court-appointed attorneys — to implement a plan to make sure attorneys could give adequate attention to their court-assigned clients.

More than a year later, the changes have not made as much of a difference as hoped, according to attorney Bill Pfeifer, who serves as administrator of the MIDC plans for Alpena, Montmorency, and Alcona counties.

Previously, three attorneys — Ron Bayot, Mike Lamble, and Pfeifer — were contracted to handle the indigent defense cases in Alpena and Montmorency counties, in addition to maintaining their private practices.

Six additional attorneys have been added to the roster, but none are willing or able to join the regular attorney rotation. Some have only agreed to take a certain type of case — only capital crimes, for instance, or only misdemeanors or traffic offenses — and some are only available at certain times or are not qualified to handle higher-level cases.

The majority of indigent cases are still handled by Pfeifer, Lamble, and Bayot. To help further lighten the load, Pfeifer has asked lawyers from Gaylord and Grayling to consider covering indigent cases in Atlanta.

An alternative to contracted attorneys struggling to fit indigent work into a private-practice schedule is the formation of a public defender’s office, which would employ a full-time staff available to visit the jail, counsel clients, research defense options, or file motions.

A public defender’s office hasn’t been formally proposed for the region, but Pfeifer anticipates that discussion will happen at some point.

“We haven’t got as many people involved as we had hoped would get involved,” Pfeifer said. “Since that’s not occurred, it’s time to maybe re-examine how we deliver services locally.”

NOT STANDING ALONE

Lawmakers created the Indigent Defense Commission in response to a study that condemned Michigan’s public defense services as “a constitutional crisis.” It meant innocent people went to jail: Inadequate defense contributed to about half of Michigan’s overturned convictions listed in the National Registry of Exonerations.

The commission has created several new standards for court-appointed attorneys representing adult criminal defendants and distributed $86.7 million statewide in 2018 — including the more than $400,000 to Alpena County — to help counties and other court systems meet those standards.

While a lack of attorney commitment has turned out less-than-ideal levels of improvement in Alpena County, some positive movement has resulted from local counties’ compliance with MIDC-established standards, attorneys say.

Applauded by attorneys, prosecutors, and judges as a substantial improvement in the past year: Attorneys are now present at all arraignments, the first court appearance at which the arrested person is formally told of the charges against him or her.

James Gilbert, one of two primary attorneys who handle indigent cases in Presque Isle County, didn’t understand the value of the new requirement until he began attending arraignments.

The attorney said he’s been able to provide crucial information and guidance for people terrified by their first encounter with the court system.

At the arraignment, the judge often establishes a bond amount, which determines how much someone has to pay to be allowed to leave jail. Without an attorney’s guidance, a defendant may end up staying in jail because they don’t know how to tell the judge the information that’s needed to set a reasonable bond, Pfeifer said.

Setting bond is one of the most important moments in a defendant’s court experience, said Loren Khogali, executive director of the MIDC.

People without an attorney to help them obtain a fair bond can lose jobs, homes, family support, or even their child’s ability to get to school, Khogali said. She likened it to tossing a pebble in a pond.

“You get that initial ‘kerplunk,’ but then there are all these rings that radiate off of it,” she said. “When someone is unnecessarily detained, it has tons of collateral consequences.”

OTHER BENEFITS

An increase in pay for attorneys was meant to counter the problem, encountered by many contracted-attorney public defense systems across the state, of lawyers paid a set rate no matter how many indigent cases they had to address in a year.

In Presque Isle County, Gilbert remembered covering a full murder trial, which takes months of preparation and scores of motions and hearings, and being paid only $2,000.

“It was always interesting work,” Gilbert said. “It was just that, when did you have time to work, considering that the compensation was so low?”

Using MIDC funds, Alpena County now pays appointed attorneys on an hourly instead of annual basis, hopefully offering attorneys an incentive to pursue all avenues of defense doggedly.

The state money has also been used to install videoconferencing systems in courthouses and jails, build rooms in jails and courthouses for private attorney/client meetings, fund attorney trainings, and pay for expert witnesses to speak on defendants’ behalf.

Before 2019, training beyond law school was not mandatory for defense attorneys. New training opportunities and money to attend that training has been a powerful component of the changes instituted by the MIDC, according to Gilbert.

Likewise, investigators and experts, always within reach of the prosecution, have, in the past, been an impossibility for indigent defense attorneys.

A prosecutor, Gilbert said, can send a sheriff’s deputy out to take measurements, look at lighting, and do other investigative work.

“On the defense side, I was the one out doing it,” Gilbert said.

Instead of petitioning the court for county funds to pay for an investigator, which may or may not be granted, MIDC money now pays for the experts who could provide proof of a defendant’s innocence.

‘COULD RUN US RAGGED’

Given the changes to indigent defense in the past year, defense attorneys “could run us ragged,” said Ed Black, former Alpena County prosecutor.

Black, recently named 26th Circuit Court judge, said he has noticed a slowdown in the court system and increasing costs to the county in the past year because defense attorneys are filing more motions. The improved defense is a positive, he said, but it does have ramifications on the court system.

An improvement in indigent defense may mean more taxpayer money used to operate other aspects of the criminal justice system, Khogali, the MIDC director said, but “everybody’s job in the criminal justice system is to do justice. And that comes at a cost. I don’t think we can allow the cost of ensuring constitutional rights are upheld to be the driver of whether we do it.”

BIGGER CHANGES?

Alpena county now has $506,965 in new grant money — including more than $180,000 not spent from the previous MIDC grant — to pay attorneys, if willing attorneys can be found, to provide a vigorous defense for those who can’t afford it on their own.

But that may not spur enough change, Pfeifer said.

At one time, Alpena took part in an Office of Public Advocacy, a public defender-like office representing felony clients in Alpena, Alcona, Montmorency, and Presque Isle counties.

The office of public advocacy was closed after local courts were restructured by the state in 2004, and the counties went to a contract system of putting indigent cases on the backs of private defense attorneys running practices of their own.

With the introduction of new standards at the state level pushing for better representation for indigent defendants — and with hundreds of thousands of dollars in state money making change possible — the momentum may be swinging back toward the establishment of a central office for public defense, Pfeifer said.

COMING MONDAY

Check out Monday’s edition of The News for a look at how one public defender office works.